Why you should (not) buy art

What impact did globalization have on creative systems of the modern/contemporary art market? Annette Schönholzer, Director of New Initiatives at Art Basel, addresses this complex question.

Globalization changed the art world, dethroned the Western art market as its center and created an interconnected, still elitist, very lucrative and highly creative global trading system. What impact did the globalization have on the creative systems of the modern/contemporary art market? Annette Schönholzer, Director of New Initiatives at Art Basel, tried to answer this complex question by reflecting on creative systems in today’s globalized world at a panel at the Venice Biennale hosted by the Zurich University of the Arts.

Even though globalization has become a central topic in the art world and has changed the perceptions of art, artists, artistic practice and relationships of all those involved in the art world, globalization by no means has made the art world flat! It offers many opportunities, even if it comes with many pressures on all commercial and non-commercial levels. While interaction, fluidity and inclusiveness increase on a superficial level, it has to be noticed that, at the same time, the art world has become a very complex place to navigate where inclusiveness and exclusiveness play an eminent role.

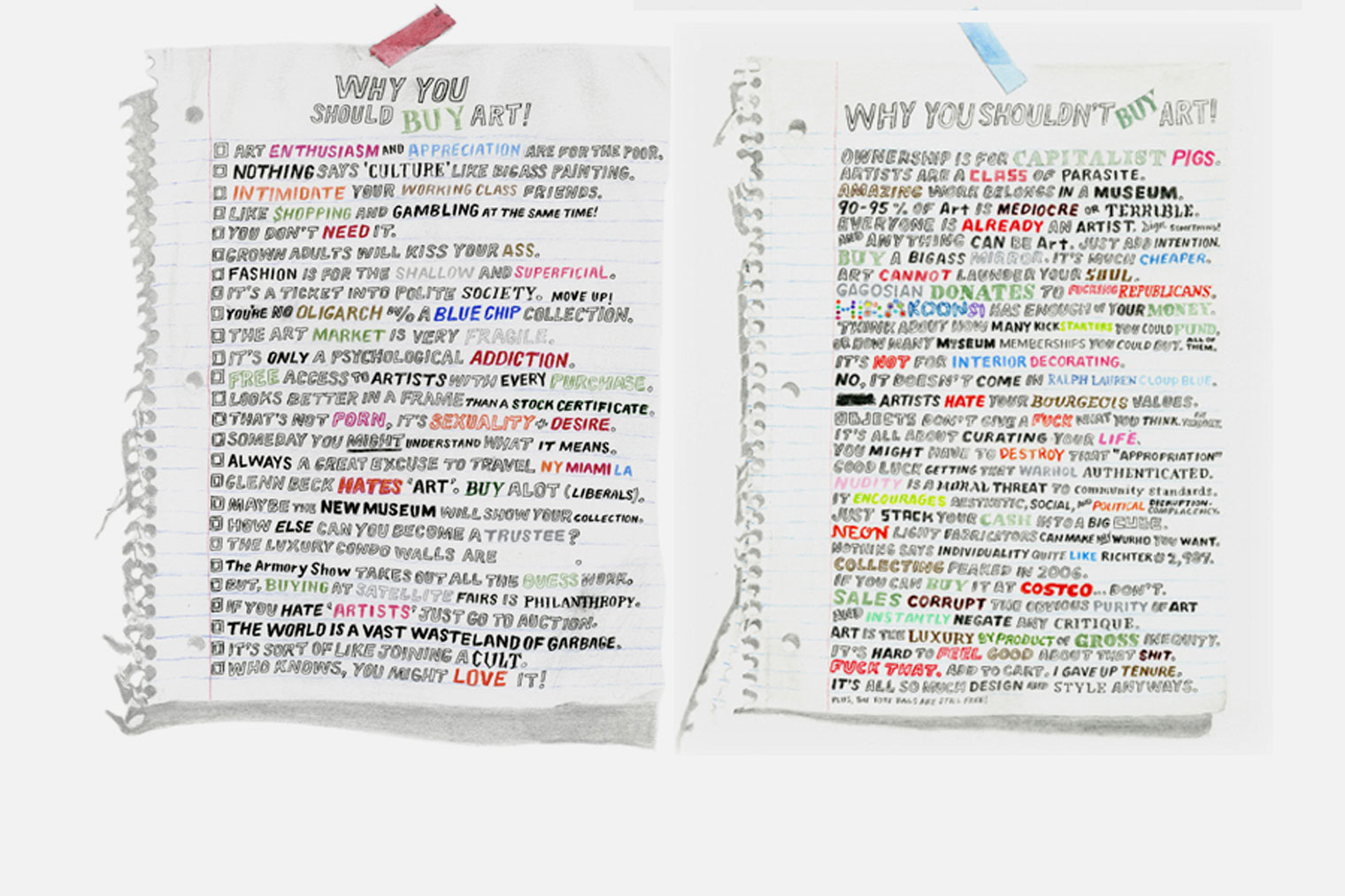

I focus on addressing the creative systems of the classical modern and contemporary art market through art fairs and auction houses, rather than the whole art system itself. To illustrate my presentation, I’d like to use the artwork of New York artist William Powhida, born in 1976, who is known for his critical view on the contemporary Western art world. It is no coincidence that I chose a rather sarcastic artist who follows the “rules of the game” in the Western art market, but at the same time scrutinizes the “who is who” of the complicated art market and the mechanics of the art system.

Art vs. money – what is the value of an individual artwork?

What does “value” in the art world mean and who determines it? As innovation and creation are essential to the art system itself, it is obvious that the creation of “value” is closely linked to the creative production of artwork itself, which is the tangible product that is at the core of all transactions. The belief in the uniqueness of the artist’s expression, of the individual artwork, which only allows limited access for its potential and interchanging owners, is a main driving force of all art market developments.

However there are important changes that have to be taken into account when talking about recent developments like the following trends: a widespread encroachment of auction houses, influx of new consumer money, emerging market billionaires, the desire of celebrities to affiliate themselves with the art market and superstar artists such as Jeff Koons, Gerard Richter or Damian Hirst. Those are just a few impacts that stimulate arguments and speculations about the pricing of art in an overheated art market. In 2013, the most expensive artwork by a living artist (Jeff Koons) ever to sell at an auction reached a price of 58.4 millions USD. As for deceased artists, Francis Bacon’s triptych, Three Studies of Lucien Freud, is now the most expensive artwork ever sold, having fetched 142.4 million USD during Christie’s contemporary auction in New York in 2013. But although these numbers amaze and are indicative to the current trend, how interesting is it to speculate on the reasoning for this in the content of the whole art market, where sales numbers are not disclosed and an overview is quite impossible?

How art galleries and dealers adapted to the new situation

The gallery model was established in the late 19th century in France where it might have answered to the artists’ and collectors’ needs. But the question is: does it still work today? Nowadays close social relationships between dealer, artist and collector are indispensible to make the gallery model work. Running a gallery is a fairly volatile business and although there exist a few mega-galleries with over 100 employees such as Gagosian, Hauser & Wirth or Zwirner, the vast majority of galleries are small or mid-sized entrepreneurs with a team ranging from five to ten people. Globalization forced particularly the Western galleries to undergo a drastic assessment of the known and unknown and to make some very difficult choices and decisions about how to continue their business.

Until recently it was still feasible for a mid-range Western gallerist with about 15 years of experience in the Western, international business to have a gallery in a city like New York, London or Berlin. But as the economies shift and the opportunities arise, artists’ loyalty has decreased and the poaching of artists by other galleries has increased. This pressure of geographically extending to a widespread range of collectors often forces gallerists to participate in a lot of different art fairs every year. They have to increase the diversity of their artists list and at the same time open additional galleries around the world. All of this may increase sales, but the immense overheads often distract from and corrupt one of the critical features of a “good” gallerist’s integrity: The search, support und development of younger, less established artists.

Art Fairs – The Solution or Only Another Nail in the Coffin?

Art fairs are huge market platforms that were established by gallerists in Central Europe in the 70s and that have multiplied and spread to the most remote places over the past ten years. They have become an important platform for the exchanges of the protagonists of the art world, meeting places with highly sought opportunities for knowledge exchange, networking and launching collaborations. But as the often quoted Pierre Bourdieu states: “Commerce needs to be negated in the field of cultural production.” A fair, by contrast, emphasizes by its very nature the commercial aspect of the gallery, but also undermines the role that galleries play in marketing a work of art or an artist, establishing its economic value and controlling its future biography.

I should not neglect speaking about the role of collectors. It is to mention that besides the inflated pricing of many artists and their work, it is primarily the West who appears threatened by this shift. What formerly was considered the unrivalled responsibility of public institutions; namely to define, build, preserve and present the canon of “remarkable art”; is under assault by a trend of collections of “recognizable” art, which are made widely accessible to the public by the increasingly active privates in privately held but publicly accessible institutions. This is particularly the case in Asia, specifically in China, where public institutions are few and private museums spring up in heaps where the finally accessible art canon is being formed by subjective, sometimes random choices. The overwhelming pressure of continuous production for the market is often the reason for individual artistic practice to be diluted and changed the notions of what “success” as an artist means in this day and age. Of course the Internet is a big player when it comes to shifts on the perception and distribution of art. Especially social media platforms, where opinions are shared and created, had a great impact on the increasing amounts of art that are sold to unknown buyers.

Worldwide Art Industry – Who Is In, Who Is Out?

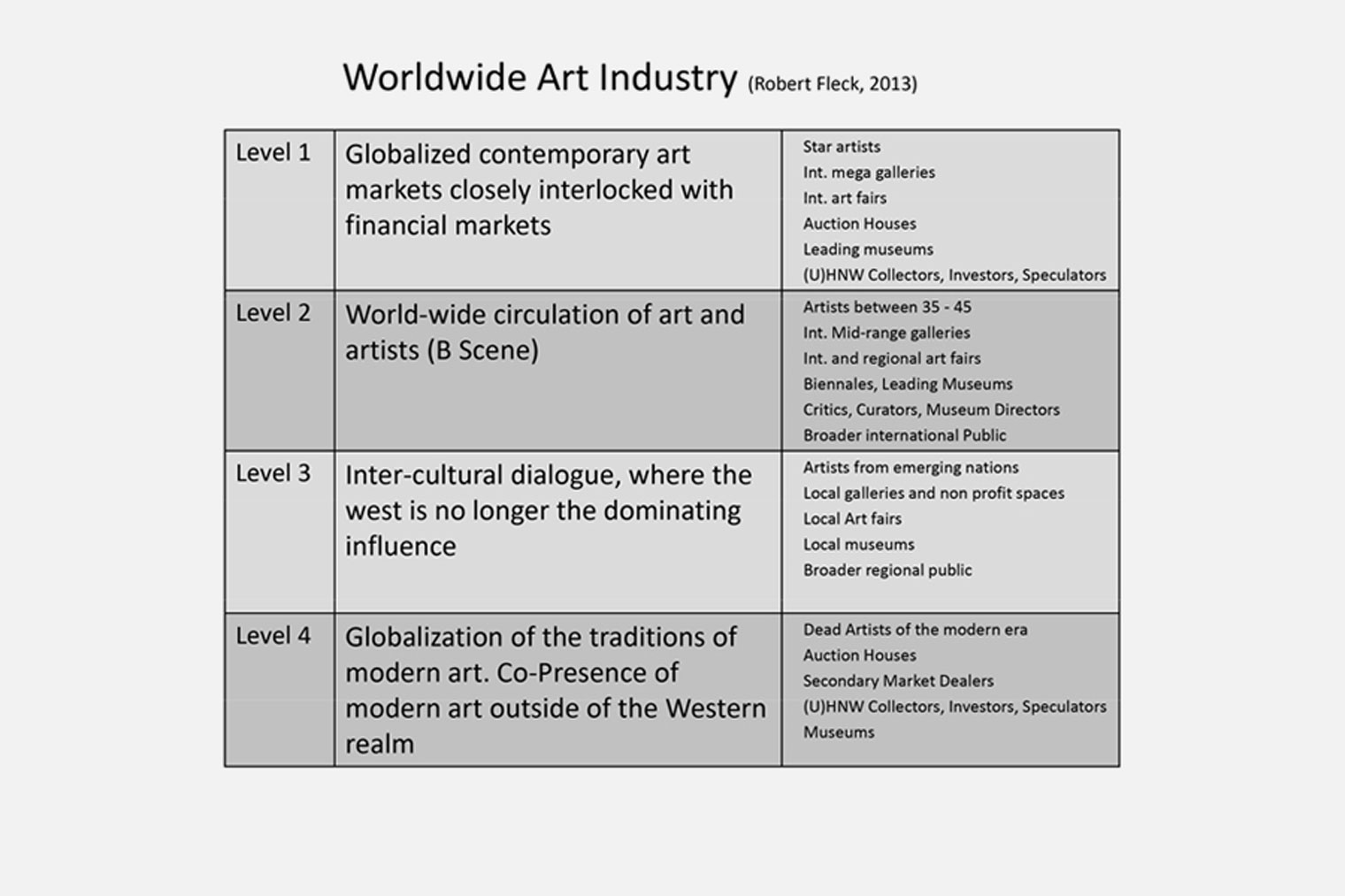

Having said so much, and so little, I would like to turn to a very useful description offered by the Austrian Professor Robert Fleck, who teaches “Art and Public” at the art academy in Düsseldorf. I have tried to summarize the introductory chapter in his book “The art system in the 21st century” – which outlines the various levels of the art industry in our day and age - in the following overview.

Fleck distinguishes between four levels of the art industry

- At the top level are the globalized contemporary art markets that are closely interlocked with financial markets – and therefore highly dependent on the ebb and flow of the global and regional financial market movements. Art Basel mainly operates within this level. The protagonists include what is considered the elite of art professionals, distributors (meaning dealers and auction houses) and buyers. The increase – or decrease – of value (cultural, economic, societal) is highly dependent on a broad array of interactions between the protagonists of the art system within this level. Art Basel applies three categories to distinguish these most prominent groups in the art market: Firstly, at the core of an art fair there is the “buying art world” (private and public collections, museums, gallerists etc.). Secondly, and of equal importance to the fabric of the market, there is the “non-buying art world” (curators, critics, the media, artists themselves of course, etc.). And thirdly, a recent phenomenon coming out of the increase of wealth in the emerging markets worldwide, the “buying non-art world”. This group consists of the super or ultra high-net-worth-individuals with little knowledge of and dedication to the art world at large, often with a mind to speculative investment and to access the cultural elite. To emphasize on those two last words – cultural elite – I’d like to quote the cultural economist Michael Hutter who said in 2007: “Acquiring art, particularly from an established gallery, is an act that not only confers the property rights on an object, but also grants access to a club distinguished by a specific aesthetic quality”. Beyond this, I would argue that for many collectors, the purchase of art is strongly connected with a personal relationship with the biography and personality of the artist. Acquiring a piece of art is like owning a piece of another person’s life, a person, who by radical choice takes the risk of exposing himself daily through creative production. In a risk adverse environment, this is a position that not many people are willing to take themselves, and therefore radiates a fascination that is quite compelling. Today, creative production and transactions at this 1st level follow an elaborate orchestration and choreography amongst the main protagonists. Playing by the unwritten and constantly shifting rules of the art market system is crucial for (economic) success. Whilst Art Basel represents the majority of what can be considered the “top” of the art market, it has little involvement in the interactions with the broader base, the “Unterbau” of the art world. There is an increasing resistance to the overpowering elite of the art world, to its influences and a tendency of segmentation among the various art system representatives.

- The second level is called the “B-Scene”, which describes a worldwide circulation of art and artists. A very important feature of this scene is its presence at the over 200 international and regional Biennales worldwide. Although those Biennales are mainly supported and financed through government subsidies, corporate sponsorship, private collectors and heavily through mid-range galleries, paradoxically, many of the artists and curators active at this level defend critical views on globalization. So-called political art plays an important role at these Biennales, which attract hundreds of thousands of viewers.

- At the third level an intercultural dialogue that has been emerging over the past 30 years. If only 20 years ago, 90% of the actors in this field were male, white and Western, today the perception at this level is that the West is no longer the political and economic center of the world. Whereas in the 50s and 60s appropriating a “western style” was a necessity for foreign artists abroad, today we can see a co-presence of artistic aesthetics and artists deriving from their local traditions and backgrounds. It is within this level where creative innovation is probably most strongly represented, although it often has not yet surfaced to a broader context.

- According to Prof. Fleck, the fourth level has very little to do with the worldwide art industry or current artistic production as such. It is however noteworthy, that there is an acceptance of parallel artistic developments in different countries within the classical modern period, which was more or less unrecognized until 1975. These developments are now being re-visited and are receiving international acknowledgement.

The future of the art system

Young artists, today, have to choose where they want to position themselves within the 3 upper levels Prof. Fleck describes. So for today’s protagonists in the art system, globalization leads to an emphasis on local ties and a re-evaluation of physical distance. Whereas artists move from country to country, living and working in multiple places with a certain fluidity, artwork with its inherent physicality must pass geographical, cultural and political boundaries to reach its audiences. Unfortunately, artworks are often subject to censorship and transactions because of heavy taxation issues.

I would like to wrap up my presentation with some examples of how globalization can be observed on the top level of the art market:

All those examples are far from being special today, but ten years ago would have been extraordinary exceptions. Some of them may seem absurd, some quite exotic and others promising. But they do depict the ways in which the art system, for better and for worse, adapts to and embraces a globalized world. Thank you very much for your attention.

- My first example is an Indian artist represented by an Austrian gallery is exhibited in Hong Kong and sold to a Brazilian collector, who has the artwork shipped to his holiday home in Miami Beach, because the tax rates on luxury goods in Brazil are far too high.

- The second example is an Italian Gallerist with galleries both in Tuscany and Beijing who works with an African artist to produce a piece made of Murano glass, which will be exhibited in the Beijing Gallery.

- Or an Australian collector couple who buys an art piece by an Australian artist exhibited by an Australian gallery that is participating in the Art Basel show in Basel, Switzerland and consequently ships the piece back to Australia.

- The last example is an Albanian artist, who lives mostly in Berlin and completed his post-graduate studies in France, represents France at the last year’s Venice Biennale (Anri Sala), whilst an international group of artists, including the celebrated political Chinese artist Ai Wei Wei, represents Germany.

All those examples are far from being special today, but ten years ago would have been extraordinary exceptions. Some of them may seem absurd, some quite exotic and others promising. But they do depict the ways in which the art system, for better and for worse, adapts to and embraces a globalized world. Thank you very much for your attention.