In the Eye of the Storm

“Sensory Hacking” at ZHdK: Looking back at three Workshops and a Symposium

Towards transdisciplinary cooperation

The Toni Campus is better than its reputation. Is it as impersonal, anonymous, and cold as often lamented? Well, only at first sight. If one spends a while in the entrance hall at one of the coffee tables, it doesn’t take long until familiar faces show up. The coffee bar is a genuine networking point. “It’s like Facebook live”, a young musician friend remarks (she’s arranged to meet a pianist for a rehearsal). Shortly afterwards, one of the Design Museum’s curators walks past. She gives me a private tour of the Open Exhibitions Division down in the basement, where I also get an insight into the theatre workshops. What an efficient place this is for social and cultural updates.

But is it also efficient for teaching? At its new Toni Campus, ZHdK has gathered its various disciplines, previously scattered across town, on one site to promote transdisciplinary cooperation among students and — ideally — to provide the emergence of new forms of art with the necessary space. Does this work? If so, how? If not, why not?

To explore such questions, the Department of Cultural Analysis, headed by Christoph Weckerle, organized a three-part further education event (as a joint venture of CreativeEconomies ZHdK, RISE Management Innovation Lab, University of St. Gallen, and the Critical Thinking Initiative of the ETH Zürich). Launched in 2015 with the “Leonardo Express”, an event focused on digitization, the series will conclude in 2017 with a seminar on “The Future of Judgment.” These two events framed “Sensory Hacking,” three workshops held from 8–11 November 2016 that ended with a symposium “on art and strategy relating to the future of higher art education.”

Created by Serge von Arx, a qualified architect, stage designer, and head of scenography at the Norwegian Theatre Academy/Østfold University College (NTA), Fredrikstad, who worked as a guest curator in Zurich, “Sensory Hacking” aims to subvert strategies designed on the drawing board through sensory-pragmatic action or rather to anticipate such strategies. In ZHdK’s case, though, the building itself can be seen as a strategy. It calls upon the various arts to draw closer. Literally, spatially: why not merge to create a total work of art if distance is suspended?

Exploring new strategies

A brief review of the beginnings of “Sensory Hacking”: In April 2016, Serge von Arx was invited to “hack” the Toni Campus with his students because the strategy devised for the building didn’t seem to be working out as planned. Future artists usually avoid transcending the confines of their disciplines. Deploying small interventions, the Norwegians hence sought to pierce the existing boundaries. They exploded the hortus conclusus of the

Department of Music by channeling the sounds emerging from instrumental lessons into the staircases and corridors: suddenly these otherwise empty spaces became filled with sound. Colorful wooden elements were positioned in the cascade, the monumental central staircase whose potential as a meeting place had barely been exploited thus far: now, passers-by began sitting on the stairs, picnicking and chatting.

These were merely two examples, among many others, that revealed that a dynamic can by all means be orchestrated. Or, put differently, that various subjects and disciplines are very much inclined to actively take notice of each other and to communicate — provided the circumstances are favorable. (Unfortunately the Norwegian interventions were swiftly removed after von Arx and his students had returned home and hence remained largely inconsequential.)

Practice takes priority

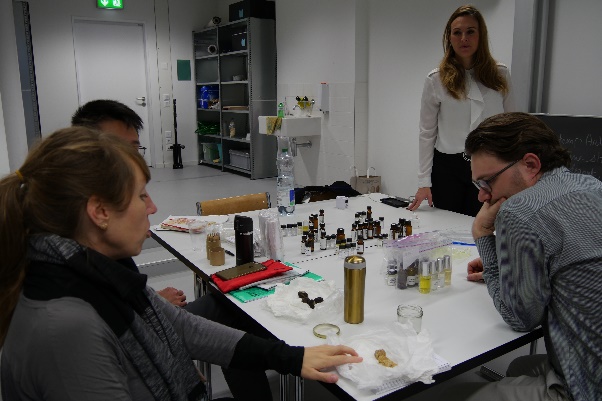

“Sensory Hacking” also set about taking over content. Students from all departments were now going to join forces. They could choose from three workshops, each run by international authorities in their respective fields: “Food and Power” (Kjartan Fønstelien, an Oslo-based archaeologist and chef); “Street Rituals” (Tony Hall, a Trinidadian carnival specialist); and “Olfactory Architecture” (Céline Barel, a New York-based IFF perfumer).

As Serge von Arx highlighted at the workshop opening, sessions weren’t about achieving presentable results. Instead, the motto was to ensure the greatest possible openness. True to its etymology, practice took priority: doing, making, producing. According to von Arx, “hacking” is about achieving maximumeffect with minimum effort. Thus, actions instead of theories were called for. Ideally, a strategy of sorts can only filter out of practical action. The motto: “Back to Basics.” This means, directing attention toward discovering that point that distinguishes itself from its surroundings without already being art. Finding instead of inventing, eliminating instead of adding. (“Everything we make is already too thick,” observed von Arx citing architect Louis Kahn.) The senses served as a compass. “Sensory hacking” also meant outsmarting the intellect with sensuousness.

So for three days the groups prospected and explored the terrain. With Kjartan Fønstelien they bent over whatever traces junkies had left on the ground. Tony Hall’s group discovered a river monster in the waters of the Limmat. And students working with Céline Barel scratched the glossy surface of the perfume industry until they reached the animal “reptile part” of their brains.

A tightly-knit community

A brief digression on attendance. To be clear: apart from the three NTA graduates who traveled to Zurich from the far north, numbers left much to be desired. Why was this? Distinguished experts from across the world, who, besides their expertise, turned out to be great personalities, made themselves available for a whole week — and yet barely anyone turns up. This is, beyond any doubt, a pity and ought to make ZHdK review its position on such events. Still, I wouldn’t speak of a missed opportunity. Those who grabbed the chance benefited. Voluntariness fosters motivation. Besides, hackers are never a mass phenomenon but a tightly-knit community.

Conspirators: that’s exactly how we felt when we tested the perfume dispensers one late evening in the empty corridors with the janitorial staff (the various gentlemen, intent on not setting off the alarms, turned out to be ingenious and amusing conspirators). Or up on the Campus rooftop, amid torrential nightly rainfall, when we helped Kjartan, the daring chef, a full-blooded Viking, to barbecue two beef filets, whose smell penetrated the protective tin foil. The experimentees reaped a delicious reward, also beyond satisfying their taste buds. Eating as a metaphor: the workshops provided inspiring food. Far from accidentally, though: after all the symposium flyer boasted a photograph of the re-enacted “Last Supper.”

(“Leonardo revisited” was how “Sensory Hacking” casually drew a line back to the “Leonardo Express.”)

What did the workshops offer? The rooftop filet matched — the paradox was intended — the budget of a prison menu (accordingly, the portions were frustratingly small). The ingenious arrangement of decorative mirrors also evoked the prison setting: as a reinterpreted panopticon it threw the guests back upon themselves. A minimal stratagem with an intentional kill-joy effect (watching oneself chewing isn’t an appetising sight). “Food and Power”: Kjartan Fonstelien and his group celebrated the handling of food in improvised kitchens as a quasi-archaeological art, which brought us consumers into contact with the lower strata of society. Concretely, the students documented the eating habits of junkies by shooting a series of photographs at a drug-trafficking spot and by affixing these onto our menu, prosaically adorned with household paper, at our evening gatherings. Not particularly amused, we downed these artfully alienated snapshops — unappetising leftovers — with lukewarm canned beer. The nauseating scent of cheap oil will probably have caused digestive problems despite the fancy surroundings of the cascade foyer.

Going beyond reason

Tony Hall and his group explored life underground, researching local “street rituals” — or rather their disruption. They fanned out along the river, heading toward the city centre, until they noticed a body of swirling water at Walchebrücke/Neumühlequai. What lay hidden there? To direct attention toward the phenomenon, a student in diving gear was sent ahead. Wetsuit, flippers, a snorkel: a barely inconspicuous sight on a rainy autumn afternoon. Though few people were around, they stopped to look. Passers-by let themselves be drawn into conversation. No one, however, was able to say what was causing the swirl. The diver was advised not to enter the water to find out more. And yet the request was not doubted for one second.

The performance worked. But is that what it was? The experimentee shouldn’t just play a role, Tony Hall had pointed out during the preparations. Only thus could something emerge that was real at the moment. Of course no river monster exists, least of all in sober-minded, rational Zurich. But the fearful pleasure triggered by the swirl and the diver struck some passers-by as monstrous enough.

Tony Hall didn’t psychologize the experiment whereas Céline Barel penetrated the human psyche. Her work involves influencing the emotional sphere — with material properties. A scent, even though we don’t conceive of it as material, is “built” from molecular components, as technical jargon puts it. Chemistry instead of alchemy. Of the three workshops, “Olfactory Architecture” was the most conventional, but also the one that enabled participants to acquire most hard-and-fast knowledge and to translate it into practice. The expert perfumer, endowed with an absolute sense of smell, introduced participants to the world of essences, their classification, the necessary vocabulary (nonprofessionals struggle for words when challenged to express olfactory experience). The perfume apprentices then devised and “built” two fragrances. Finally, they perfumed the building with these creations and obtained feedback via questionnaires. The fact that some spontaneous reactions were quite aggressive probably had to do with the misperceived signals: the sweet coziness of a bakehouse and a husky open fireplace atmosphere amid ZHdK’s exposed concrete are confusing. And no one likes to be given the (olfactory) roundaround.

Hackers are innovators

So far, so good. However, the three productive days were not followed by a detailed debriefing (how come it was forgotten?), but concluded with the final symposium. That the exploratory, process-oriented nature of the event was somehow lost in the workshop presentations is self-evident. But the fact that external speakers were invited to address the symposium somehow seemed indebted to academic necessity. Simon Grand, “management researcher, strategy designer, knowledge entrepreneur” (according to his website), at least discussed St. Gallen textile manufacturer Jakob Schläpfer as an example of a company that continuously “hacks” its routine procedures to remain innovative. In Schläpfer’s case, art (and craft) tips over into fashion (business), and vice versa — in Grand’s lecture the subject of art education, billed as part of the program of “Sensory Hacking,” at least shone through from afar. It also transpired that strategy is an elusive concept, graspable only occasionally and retrospectively. Strategies forge ahead, but no one knows the future.

Take your time, trust your intuition

After Frédéric Martel’s input focusing on smart curation and thus the fact that human beings are asserting their position in the arts and culture despite the prevailing algorithm-based “Uberisation”, it was impressive to experience just how far the real-life factor can be perceived as a threat also in art: instead of giving her scheduled paper, Sodja Lotker (Department of Theatre, Prague Academy of Performing Arts, DAMU), visibly struggled to contain her emotions and set about expressing her dismay at Donald Trump’s election. Equally aghast, though for other reasons, was Karmenlara Ely (NTA). Her energetic delivery was a fierce protest against the “relevance” helping entrepreneurial perspectives gain increasing ground at arts universities. She wrote the word “NAUSEA” in capital letters on the blackboard to remind the audience of the primal ground from which art springs: an unease about existence that must be endured. Her poetic appeal for slowness and delay amounted to claiming that the artist is in the eye of the storm: there where everything is still.

Karmenlara Ely was the only speaker to look back at the workshops (which she had attended as a participant observer). They had all been about dreaming, about that dream that comes with what she called the “sixth sense”: this, she maintained, had “hacked” the university building, the city streets, human performance for three days. Thus, we closed with a blazing speech, underpinned with philosophical reminiscences, abreast with discourse. On the panel, Tony Hall quite rightly lamented that the whole symposium had attempted “to kill the possibility of hacking.” What was needed to provide possibilities for hacking, Karmenlara Ely replied emphatically — she grabbed not one but two microphones — was “time.” In the end, “Sensory Hacking” came full circle. And yet this is where discussion ought to begin. Also at the Toni Campus.